Author

Kaitlyn Finn

Mentors

Melanie Palomares, Ph.D. and Kristin Kirchner

Psychology 228 (Laboratory in Psychology) is a capstone class for psychology majors and minors. The main goal of the course is the completion of an independent research project, which the student develops themselves from idea to data analysis over the course of the semester. The instructional team is led by faculty member Dr. Melanie Palomares and dedicated graduate students. The 2019-2020 graduate student team consisted of Wendy Chu, Kristin Kirchner, Samantha Langley, Jaleel McNeil, Jonathan Rann, and Daria Thompson.

Students were encouraged to develop a study based on their personal interests such as social media, interpersonal relationships, or exercise. Following certification in human subjects training, the students collected data by deploying surveys and assessments to their target demographic. Students analyzed and interpreted their data using SPSS, a statistical software. Students then wrote a full length, APA style research paper about their project. Students from this class acquired several skills such as responsible research conduct, survey creation, statistical software analysis, and professional writing. This class provided the opportunity for undergraduate students to preview the graduate student research experience. The students published here went the extra mile and prepared their research papers for this publication, which often included additional, more sophisticated data analysis and new research questions.

Abstract

The study at hand was designed to look into the issues of eating disorder awareness and dieting attitudes. Specifically, it was hypothesized that individuals with more knowledge of eating disorders would be less likely to believe in dieting. It was additionally hypothesized that there would be a difference in amount of eating disorder knowledge seen between pre-determined age groupings. This was hypothesized due to the nature of the inception of eating disorders as a clinical diagnosis. Eating disorders did not begin to be added as a category into the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual until the 80’s, suggesting that participants of older ages might have less knowledge about the disorders themselves. Additionally, mental health is now less stigmatized in younger generations, leading to the hypothesis that older individuals might not be disseminating and sharing information on mental health with each other. This study includes a sample of 103 participants; 93 being biologically female and 10 being biologically male, with various self-reported races and ethnicities. Participants answered an online questionnaire regarding demographic data, dieting beliefs, and eating disorder knowledge, which provided the main source of data for the study. Participants for this study were collected via social media, personal relations, and word of mouth. Analysis of the participants’ data revealed a significant relationship between eating disorder knowledge and dieting beliefs as hypothesized, meaning the more one knew about eating disorders, the less likely they were to be proponents of dieting. However, there failed to be any significant difference of accuracy of eating disorder knowledge throughout different age ranges.

The Effects of Eating Disorders on Dieting Beliefs

Both eating disorders and diet culture are prevalent in our society and are more connected than some might realize. Eating disorders have a number of causes spanning from biological, environmental, and psychological factors. Diet culture’s effect on the development of eating disorders falls into the environmental or social factors (Polivy & Herman, 2002). Westernized cultures have a tendency to idealize thinness and a specific body ideal, leading to the overwhelming amount of diet culture messages in places like the United States (Yang, 2014). While research has been conducted on individuals’ attitudes toward dieting, and separate research has been conducted on individual’s general knowledge of eating disorders, there is little information on a possible correlation between the two. The study at hand seeks to determine whether a correlation exists between dieting beliefs and eating disorder knowledge. If a correlation exists, further research could use this information to better create eating disorder prevention education as well as treatment initiatives. The aspect of utilizing age in this study may help intervention teams better target which age groups might most benefit from this type of information.

Diet culture conceptualizes many different ideas. Diet culture can, all at once, conflate size and health, put morality onto food (i.e., “good and bad foods”), create and perpetuate thin privilege, maintain fatphobic rhetoric, and make rules for those to follow rigidly regarding food and movement (Chastain, 2019). Diet culture can appear in multiple forms such as anti-fat propaganda, sizeist prejudice, and idealization of thin bodies (Polivy & Herman, 2002). Diet culture and positive attitudes toward dieting, including the dissemination of information about thinness, fad diets, and diet products, are pervasive in cultures worldwide (Yang, 2014). Dieting beliefs have progressed in mainstream society so that an average individual might not view diets as disordered eating or a precursor to a full-blown eating disorder, despite research stating that not only can diets lead to eating orders, but that diets are, at most, only 5% effective (Derenne & Beresin, 2006). Prior research has shown the majority of medical professionals (59%), felt as though they were not equipped to recognize an eating disorder (Linville, Brown & Oneil, 2012). It can then be theorized that the normalcy of dieting might lessen the ability to recognize disordered eating by medical professionals or that medical professionals are not properly informed about eating disorder causes. If medical professionals are not knowledgeable about the topic in question, it might be thought that laymen would have even less knowledge, as is being examined in this study.

It is then the purpose of this study to investigate the level of eating disorder knowledge and the beliefs of dieting held by willing survey participants. With the present research providing information about the effect of diet culture, or a positive attitude toward dieting, on the possible development of eating disorders, there exists a logical argument in the idea that knowing more about eating disorders, including possible causes like diet culture, would result in more negative views of dieting. Thus, the hypothesis in the present study states that the more that an individual knows about the details of eating disorders, the more negative dieting beliefs that individual will hold, since knowing that dieting can be a causal factor in eating disorders could logically lead an individual to show negative attitudes to such a factor that causes the most deadly mental disorder in the United States.

Method

This project and its contents were approved by Kristin Kirchner and Melanie Palomares of the University of South Carolina, and all researchers involved had completed CITI’s Human Subjects Research training. All subjects completed informed consent. Data was anonymous and had no identifying details provided by the participants. Sensitive information was not gathered, and protected populations were not surveyed. The original root of this data was to fulfill requirements for a psychological research methods class (PSYC228) at the University of South Carolina, Columbia.

Participants

Participants were recruited via social media (including Instagram, Groupme, Facebook, and Twitter) as well as word of mouth or text message conversations. The present study initially recruited 103 participants. Participants were sorted into age groups based upon what generation they were a part of: “Gen Z” (18-24 years old), “Gen Y/Millennial” (25-40), “Gen X” (41-56), or “Baby Boomer” (56+). Participant information can be found in Table 1. Age groups were determined based off of the proposed hypothesis that different generations would have different levels of knowledge about eating disorders. Nine of these participants were later excluded from data analysis due to incompletion of the survey, bringing the total participants analyzed to 94. Each participant digitally agreed to the informed consent statement in the beginning of the survey. Participants were not given any incentives for completing the survey.

Materials

The main apparatus in this study was a Google Forms survey, accessible by phone or computer. The survey comprised of two different existing psychological tests and additional questions added by the researchers to enhance possible responses for better interpretation of results. There was a total of 50 questions. The survey was split into three sections: demographic questions, dieting beliefs questions, and eating disorder knowledge questions. Demographic questions asked about age, biological sex, class level, race, current happiness level, and days per week of exercising more than one hour. The second section, regarding questions of dieting beliefs, included the use of the Dieting Beliefs Scale (Stotland & Zuroff, 1990) and researcher-made questions. All questions in this section are scaled on a Likert scale of either 1-5 or 1-7. The higher the score on these questions, the more positive the dieting attitudes. The third section, regarding questions of eating disorder knowledge, used the Eating Disorder-Specific Knowledge Questionnaire (Girz, Lafrance Robinson & Tessier, 2014) along with researcher-made questions. The questions in this subsection are all true or false questions which were scored by correctness. The more correct answers reflect a higher level of knowledge about eating disorders. The survey can be found in Appendix A.

Procedure

Participants responded to questions on a Google Form which outlined their participant rights and proceeded with questions on demographics, dieting beliefs, and eating disorder knowledge, in that respective order. Participants who skipped any question were excluded from the statistical analyses. The survey was estimated to take between five and ten minutes. Each question was presented one at a time on the screen, with the participant having to press an arrow to go to the next page. Once the survey was completed, the participant clicked a button labeled “submit” to send responses to the researcher. They were then directed off the page.

Results

Statistical tests, including Pearson’s correlation and a between-subjects ANOVA, were run on the collected data using IBM’s SPSS v20, allowing for the analysis of dieting beliefs and eating disorder knowledge as well as age group differences of eating disorder knowledge and dieting beliefs.

A one-way, between-subjects ANOVA was conducted on eating disorder knowledge question scores between the age groups of Gen Z (M=10.96, SD=2.59), Gen Y/Millennials (M=11.08, SD=2.78), Gen X (M=11.06, SD=1.66), and Baby Boomer (M=10.5, SD=3.11). The test found no significant difference between age groups’ relative knowledge of eating disorders, F(3,89) = 0.068, p > 0.05.

A one-way, between-subjects ANOVA was conducted on dieting knowledge between the age groups of Gen Z (M=54.96, SD=15.77), Gen Y/Millennials (M=49.64, SD=16.78), Gen X (M=54.61, SD=16.08), and Baby Boomer (M=54.5, SD=18.30). The test found no significant difference between age groups’ dieting knowledge, F(3,89) = 0.630, p > 0.05.

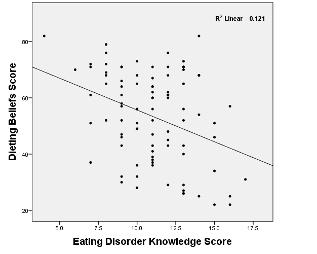

A simple linear regression was conducted to predict dieting belief scores (M=53.44, SD=16.099) based on eating disorder knowledge scores (M=10.99, SD=2.478), b= -0.348, t(91)= 10.885, p < 0.001. A significant regression equation was found (F(1,91)= 12.523, p < 0.01, R2 = 0.121). Changes in the predictor variable (eating disorder knowledge scores) were significantly associated with changes in the response variable (dieting belief scores). A scatterplot depicts the association between dieting belief scores and eating disorder scores (Figure 1)

The calculated Chronbach's alpha for the dieting beliefs questions was .68, consistent with that of the Dieting Beliefs Scale (Stotland & Zuroff, 1990). The Chronbach's alpha for the eating disorder knowledge questions was .446.

Discussion

Researchers originally hypothesized that dieting beliefs and eating disorder knowledge would result in a negative relationship; meaning that the more an individual knew about eating disorders, the less likely they would be to engage with dieting beliefs. Findings of the statistical analysis suggest that a significant regression equation between the two variables exists. Prior research states that dieting or buying into diet culture is one of the many potential causes of eating disorder development (Polivy & Herman, 2002), suggesting that those who know the causes of eating disorders will not have a positive outlook on dieting, as was exhibited as true in this study. These findings provide hope that as more information about eating disorders is disseminated, less people might fall into the fallacy of dieting and risk possible development of a life-threatening eating disorder (O'Connor, Simmons, & Cooper, 2002).

The additional hypothesis to this study was that there would be a significant difference in eating disorder knowledge between age groups. This assumption was due to the nature of eating disorder knowledge history as it relates to the age groups in the study. For reference, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) did not include anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa until 1980 in the DSM III, and binge eating disorder, which is the most prevalent eating disorder to date, was not added to the DSM V until 2013 (Eichen & Wilfey, 2016). The lateness of the societal impact of eating disorder awareness could have suggested that older generations would not have the knowledge of younger generations. Conversely, this study exhibited a non-significant difference in eating disorder knowledge between generations. This could be viewed as a positive, meaning all age groups have caught up on the same amount of information, or as a negative, with the possibility that each age group is actually as equally uninformed as the next, given that even licensed clinicians do not feel comfortable identifying the illness (Linville, Brown & Oneil, 2012).

The study presents certain limitations in its creation and application. The study was limited to 103 participants, all of which were from the United States. There also lacked diversity in subjects, with the majority of them being white or Caucasian. In addition, the survey at hand relied on self-reporting, meaning researchers relied on the honesty and diligence of participants. Furthermore, the spread of participants in each age group was far from equal. It would have been beneficial to the study and consequent analysis to have the same number of participants in each age group for a more accurate comparison of eating disorder knowledge.

The present study allows for further investigation of eating disorder knowledge of the general population. It also provides valid reasoning to look into the relationship between the act of dieting and the development of an eating disorder or investigating those with preexisting eating disorders and their own thoughts on dieting. In a clinical setting, those types of findings could drastically benefit the current diet culture climate as well as better preventative education on eating disorders and disordered eating habits. It would also be of interest to eventually conduct a similar study looking at comparisons of eating disorder knowledge or dieting beliefs across various races and ethnicities to look at those concepts through a cultural and societal lens, since this study was made up of predominantly Caucasian participants. Regardless of the exact execution of further studies about eating disorders and dieting, any and all information to be learned by researchers would vastly help the field of psychology, mental health, and nutrition, leading to improvement of eating disorder prevention, education, and treatment.

About the Author

Kaitlyn Finn

Kaitlyn Finn

My name is Kaitlyn Finn and I am from Verona, New Jersey. I graduated from the University of South Carolina, where I was a part of the Capstone Scholars Program, in May of 2020 with a B.A. in experimental psychology and a minor in advertising and public relations. After graduation, I moved to Seattle, Washington to attend the University of Washington in pursuit of my Master of Social Work degree. With hopes of obtaining my masters, I aspire to become a licensed eating disorder therapist, working in a treatment center for adults and adolescents. This aspiration fueled the inspiration for my research on eating disorder knowledge and dieting beliefs. With a plethora of information on eating disorders in my realm of knowledge, I was interested in learning the level of eating disorder knowledge amongst other individuals and how that might correlate to positive or negative beliefs on dieting. This project has furthered my passion for the eating disorder field and has provided me with clinical implications that I may be able to utilize in the future. I would like to thank my mentor for this research, PhD candidate Kristin Kirchner, for all of her statistical and practical assistance on this project. I would additionally like to thank Dr. Melanie Palomares and her PSYC228 class for spearheading the research of many students like myself.

References

Chastain, R. (2019, May 02). Recognizing and Resisting Diet Culture. Retrieved January 10, 2021, from https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/blog/recognizing-and-resisting-diet-culture

Derenne, J. L., & Beresin, E. V. (2006). Body Image, Media, and Eating Disorders. Academic Psychiatry, 30(3), 257–261. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.30.3.257

Eichen, D. M., & Wilfley, D. E. (2016, May 26). Diagnosis and Assessment Issues in Eating Disorders. Retrieved April 28, 2020, from https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/special- reports/diagnosis-and-assessment-issues-eating-disorders

Girz, L., Robinson, A. L., & Tessier, C. (2014). Eating Disorder-Specific Knowledge Questionnaire. PsycTESTS Dataset. doi: 10.1037/t40114-000

Insel, T. (2012, February 24). Post by Former NIMH Director Thomas Insel: Spotlight on Eating Disorders. Retrieved March 3, 2020, from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/directors/thomas-insel/blog/2012/spotlight-on-eating-disorders.shtml

Linville, D., Brown, T., & Oneil, M. (2012). Medical Providers Self Perceived Knowledge and Skills for Working With Eating Disorders: A National Survey. Eating Disorders, 20(1), 1–13. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2012.635557

O'Connor, M., Simmons, T., & Cooper, M. (2002, November 07). Assumptions and beliefs, dieting, and predictors of eating disorder-related symptoms in young women and young men. Retrieved January 17, 2021, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1471015302000909?casa_token=yxFNF4cH2C4AAAAA%3AEKNV3rQiD0o-yWyiig03P_sqnA3ScahSv9x7hstUPQsa7x_n4PnBaOWziyrxfRgBfQ9fKgFQ-Q

Polivy, J., & Herman, C. P. (2002). Causes of Eating Disorders. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 187–213. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135103

Stotland, S. C., & Zuroff, D. C. (1990). Dieting Beliefs Scale. PsycTESTS Dataset. doi: 10.1037/t62732-000

Yang, L. (2014). The Effect of Western Diet Culture on Chinese Diet Culture. Proceedings of the International Conference on Education, Language, Art and Intercultural Communication. doi: 10.2991/icelaic-14.2014.169

Figure 1. A scatterplot showing the negative regression (r= -.348) between eating disorder knowledge scores and dieting belief scores.

Appendix A: QuestionnaireTop of Form

Questions marked with an asterisk (*) were reverse coded.

Dieting Attitudes and Beliefs Questions

Answer the following questions as honestly and truthfully as possible from “Not at All Descriptive Of My Beliefs (1) to “Very Descriptive Of My Beliefs (5)”

- By restricting what one eats, one can lose weight.

- When people gain weight, it is because of something they have done or not done.

- A thin body is largely a result of genetics.*

- No matter how much effort one puts into dieting, one's weight tends to stay about the same.*

- One's weight is, to a great extent, controlled by fate.*

- There is so much fattening food around that losing weight is almost impossible.*

- Most people can only diet successfully if other people push them to do it.*

- Having a slim and fit body has very little to do with luck.

- People who are overweight lack the willpower necessary to control their weight.

- Each of us is directly responsible for our weight.

- Losing weight is simply a matter of wanting to do it and applying yourself.

- People who are more than a couple of pounds overweight need professional help to lose weight.*

- By increasing the amount that one exercises, one can lose weight.

- Most people are at their present weight because that is the weight level that is natural for them.*

- Unsuccessful dieting is due to lack of effort.

- In order to lose weight people must get a lot of encouragement from others.*

Answer the following questions as honestly and truthfully as possible on a scale of 1 to 7.

- In the next three months, I intend to go on a diet.

- Strongly disagree (1) → Strongly agree (7)

- In the next three months, I intend to reduce my caloric intake.

- Strongly disagree (1) → Strongly agree (7)

- If I diet in the next three months, this would be...

- Harmful (1) → Beneficial (7)

- If I diet in the next three months, this would be...

- Unpleasant (1) → Pleasant (7)

- If I diet in the next three months, this would be...

- Useless (1) → Useful (7)

- If I diet in the next three months, this would be...

- Foolish (1) → Wise (7)

- If I diet in the next three months, this would be...

- Bad (1) → Good (7)Top of Form

Eating Disorder Knowledge Questions

Answer the following questions to the best of your ability (True or False)

- If you eat 3 meals per days and don't purge, you are not likely to have an eating disorder. (False)

- Individuals with bulimia nervosa always purge themselves by vomiting or using laxatives. (False)

- Individuals with anorexia nervosa do not binge or purge. (False)

- Individuals with anorexia nervosa typically look underweight. (False)

- The majority of adolescents with eating disorder come from dysfunctional families. (False)

- You cannot disclose an eating disorder diagnosis to a parent if the child disagrees. (False)

- Parents cannot be seen as the solution in the treatment of eating disorders until ways in which they have caused it have properly been explored. (False)

- It is not always advisable for parents to get tough with a child with an eating disorder because he/she will experience too much trauma and distress. (False)

- While parents are important, children with eating disorders will never get better until they receive some sort of individual therapy themselves. (False)

- It is more the parents’ responsibility than the child’s to bring their child to recovery from an eating disorder. (True)

- Adolescents need at least some motivation to be able to receive treatment. (False)

- Eating disorders are the second most deadly mental disorder. (False)

- The most common eating disorder is anorexia. (False)

- Eating disorders are developed by choice. (False)

- Purging behaviors in bulimia can include fasting and exercising. (True)

- There is more than one type of diagnosable anorexia. (True)

- Lanugo is defined as the slow processing of food in the digestive system due to an eating disorder. (False)

- The majority (more than 50%) of individuals with eating disorders seek treatment. (False)

- Those who are "obese" (by the BMI standard) have disordered eating habits. (False)

- ARFID is a subtype of anorexia. (False)