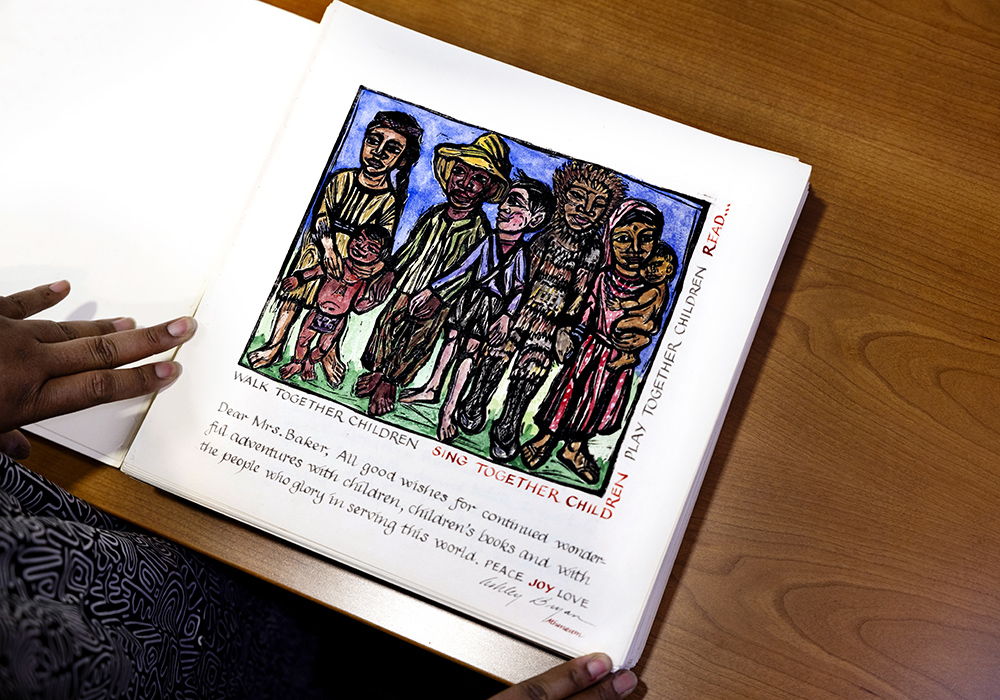

“Dear Mrs. Baker, All good wishes for continued wonderful adventures with children, children’s books, and with the people who glory in serving this world. Peace, joy, and love,” wrote author Ashley Bryan on a page beneath his illustration.

In 1974, Augusta Baker received 150 pages filled with warm dedications and original artwork from children’s authors, illustrators, publishers and library colleagues. The gift celebrated Baker’s remarkable 37-year career, marking the end of a chapter as she retired from New York Public Library.

“If anything gives an idea of just how profound her impact was, it really is this book,” says Nicole Cooke, professor in USC’s School of Information Science and the Augusta Baker endowed chair.

Shortly before her death in 1998, Baker’s son donated the retirement book along with 1,600 other books, documents and photos belonging to his mother to the University of South Carolina’s Irvin Department of Rare Books and Special Collections.

This donation established the Augusta Baker Collection of African American Children’s Literature and Folklore at USC, which tells the story of Baker’s life and her wide-ranging influence on librarianship and children’s literature. It also cemented the importance of Baker’s legacy to South Carolina, where she lived after retirement, serving as USC’s storyteller-in-residence for nearly 15 years.

“My role as Baker chair is to build on her legacy of outreach,” Cooke says. “Baker was a master storyteller. She was also a Black librarian. She was also interested in social justice. And she was interested in publishing. These are the pillars that I build upon to represent fully who Baker was.”

Black librarian and advocate

Baker was one of the first Black librarians in a leadership role in a major city’s library system, and she also held leadership positions with the American Library Association. These responsibilities gave her incredible visibility and took her throughout the country.

“When she retired, Mrs. Baker was the head of children’s service for all the branches at New York Public Library. For her to have worked her way up in the ‘40s and ‘50s – as a Black librarian, and we know what things were like then – it’s pretty significant,” Cooke says.

From the very beginning of her library career in Harlem, New York, Baker championed the cause of finding books that truly represented the lives of the children she served. Troubled by overtly racist depictions in the children’s books of the time, Baker pushed for the creation of a collection of books at New York Public Library that provided positive depictions of Black and African American culture and life.

“Part of what she’s known for is that she said, ‘I don’t like these books that I’m reading to my children in Harlem. They’re not representative of everyday life and the everyday joy,’” Cooke says.

Correcting the issue required starting from the source, and Baker worked directly with children’s authors, illustrators and publishers to raise the bar for better children’s literature.

“When she worked with people like Ashley Bryan and others in children’s literature, she really promoted a better approach. She published several bibliographies, and she said, ‘These are the books that positively portray Black children and Black life, and these are the books that I’m going to share with my children.’”

Her recommendation lists became a resource for libraries, schools and educators across the country. As her influence grew, she traveled extensively to talk to organizations about how to develop collections that better reflected the children they served.

A New Yorker moves south

Her travels took her frequently to South Carolina, where she was invited by the Palmetto Teacher’s Association to present on materials for Black children. She didn’t mind stopping in Columbia because her son, James, was posted at Fort Jackson. She also had a friend and colleague, Wayne Yenawine, who was starting up a library school at USC.

"Baker is an example of how to maneuver and negotiate in the profession as a woman of color. She was a trailblazer, and I don’t think we would be as far as we are without her work."

Yenawine, the late dean emeritus and founder of USC’s School of Information Science, originally asked Baker to join him on the faculty. He wanted the new program to have a diverse faculty and to include a focus on children’s literature, goals in step with Baker’s work in the field.

“The second I retired, I began to get these little telephone calls from Wayne,” Baker told an interviewer in 1989. “He still wanted a strong teacher… and I was not ready to come down to South Carolina.”

In 1980, the timing was finally right to move to Columbia to be closer to her son and his family – and to become storyteller-in-residence at USC, a position she held until 1994.

It was the first position of its kind at an American university, a role created for Baker to teach students, librarians and educators “how to make reading more exciting for children,” says the Columbia Record (Nov. 20, 1980).

The position allowed Baker flexibility to share her expertise with any of the departments and schools at USC as well as with other institutions and agencies state- and nationwide.

She occasionally did outreach at local schools, but it wasn’t Baker’s sole intention to work with children directly. Rather, she used the residency to share her mastery of storytelling with other librarians and educators.

Her storytelling tradition

“She had a very particular way of telling,” Cooke says. “She would light a candle, just bring the audience in and set the stage. And when she was finished, she would blow the candle out, so there was a bit of ceremony.”

Leslie Tetreault took one of Baker’s famous classes on storytelling with her colleagues at Richland Library. It was 39 years ago, and Tetreault was new to her role in the children and teen department at Richland Library, where she is now manager.

“I remember that Mrs. Baker gave us two weeks to learn a story, and she talked about the difference between folk tales, fairy tales and literary fairy tales,” Tetreault says, recalling how Baker called her out for rushing through her story when she first performed for her.

“To her, storytelling was not about histrionics or wearing a costume. It was about the color and timing and pacing and texture of your delivery. She wanted you to really understand that and master that,” she says.

Tetreault had many more years to master Baker’s live storytelling technique as Richland Library partnered with USC in 1986 to create an annual event called A(ugusta) Baker's Dozen: A Celebration of Stories.

Each spring, elementary school children gathered on the lawn of historic Columbia locations to hear storytellers perform. Originally, Baker herself was the draw for these young listeners, but the event expanded to include librarians and educators trained in Baker's style.

Baker’s legacy moving forward

Now in the 39th year of the festival, Tetreault teaches the annual storytelling training workshop. The class is structured in the same way that Baker taught her storytelling workshops decades ago. As the Baker chair, Cooke is active in planning the festival, including the annual lecture, which invites authors, illustrators and library professionals to speak. This spring, the lecture will feature Vashti Harrison, the first Black woman to win the Caldecott Medal.

Cooke says events like the festival have helped to raise the profile of USC’s Master of Library and Information Science degree over the years, especially with students looking for a program that will be supportive for students from underrepresented backgrounds.

“Librarianship is, depending on the year and what source you look at, around 82-85 percent comprised of white women who hold the degree. And it has continued to be that way over the last 25 years that I’ve been in the profession,” Cooke says. “The populations that we serve are super diverse and changing by the year, and our profession needs to reflect the communities we serve.”

To address this disparity, Cooke launched the Baker’s Scholars program, which matches funding offered to recipients of the American Library Association’s Spectrum Scholarship.

But Cooke says growing representation in librarianship will take more than recruitment programs alone: It will also require a cultural shift and inner resilience from those who are entering the field, whatever their backgrounds.

“Being a minority or from marginalized group in a very white profession, it’s hard. But Baker is an example of how to maneuver and negotiate in the profession as a woman of color. That’s what I try to pass on to my students,” she says. “She was a trailblazer, and I don’t think we would be as far as we are without her work. That said, there’s still so much to do.”